Senses of Justice After Managed Retreat: Understanding Post-Buyout Land Restoration

FEATURE

By Veronica Olivotto

Veronica Olivotto is an urban adaptation researcher who recently earned a PhD in Public and Urban Policy from The New School. Her research focuses on managed retreat, climate justice, and post-buyout land restoration in vulnerable coastal communities. She is currently working on the internal evaluation of the NATURA initiative connecting networks on urban nature-based solutions across the world. Her work has been published in journals including Frontiers in Climate, and she has been a fellow at the Urban Systems Lab at The New School.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Centering community "senses of justice" reveals how residents understand justice dimensions in post-buyout land restoration beyond technical metrics

Historical disinvestment undermines adaptation by fueling mistrust and emotional trauma after property buyouts

Residents can perceive post-buyout vacant land as a reminder of long-standing neglect—but also as space that could support community-driven uses

Immersive, trust-based research methods uncover perspectives often missed in top-down planning

Managed retreat and post-buyout land strategies must integrate housing mobility, ecological restoration, community health and deliberative engagement to be just and effective

The Roots of My Research: Global Patterns of Displacement and Water

I began to be interested in managed retreat, also called planned relocation, in 2015 when I was in the city of Cali in Colombia. I learned about how the city was forcibly removing a community of thousands of people who had settled on a dike protecting the city from flooding from the river Cauca. People settled on the dike out of the inability to find affordable housing anywhere else. The city overlooked the issue until increasing flooding caused deaths, losses, and public outcry to remove settlers from harm's way became incessant in the media.

With a friend who looked at relocation in Christchurch (New Zealand), I wrote a short piece about it titled The Threat of Water: Relocation in Cali and Christchurch.

When I moved to NYC and understood that 400,000 people live in the city's high-risk floodplain (a number larger than the entire city of New Orleans) and that the majority are low-income renters, I saw similar patterns emerging. Living in high-risk floodplains becomes an issue of climate justice because metrics like income and housing status intersect with pre-existing class and race disadvantage, leading to higher flood vulnerability for low income and black and brown communities. For instance, lesser intergenerational equity can affect the ability to meet rising insurance costs and find a comparable property after accepting a buyout.

A Framework for Understanding Multiple Voices and Multiple Justices

My PhD resulted in publishing the paper Senses of justice after managed retreat in New York city and a second paper is in progress. The term "senses of justice" refers to the ways affected people subjectively perceive, evaluate, and narrate environmental interventions and their consequences. What makes this framework powerful is its plurality—it acknowledges the many ways individuals and communities might define fairness in post-retreat contexts, whether through accountability, legitimacy, voice, or access to decision-making.

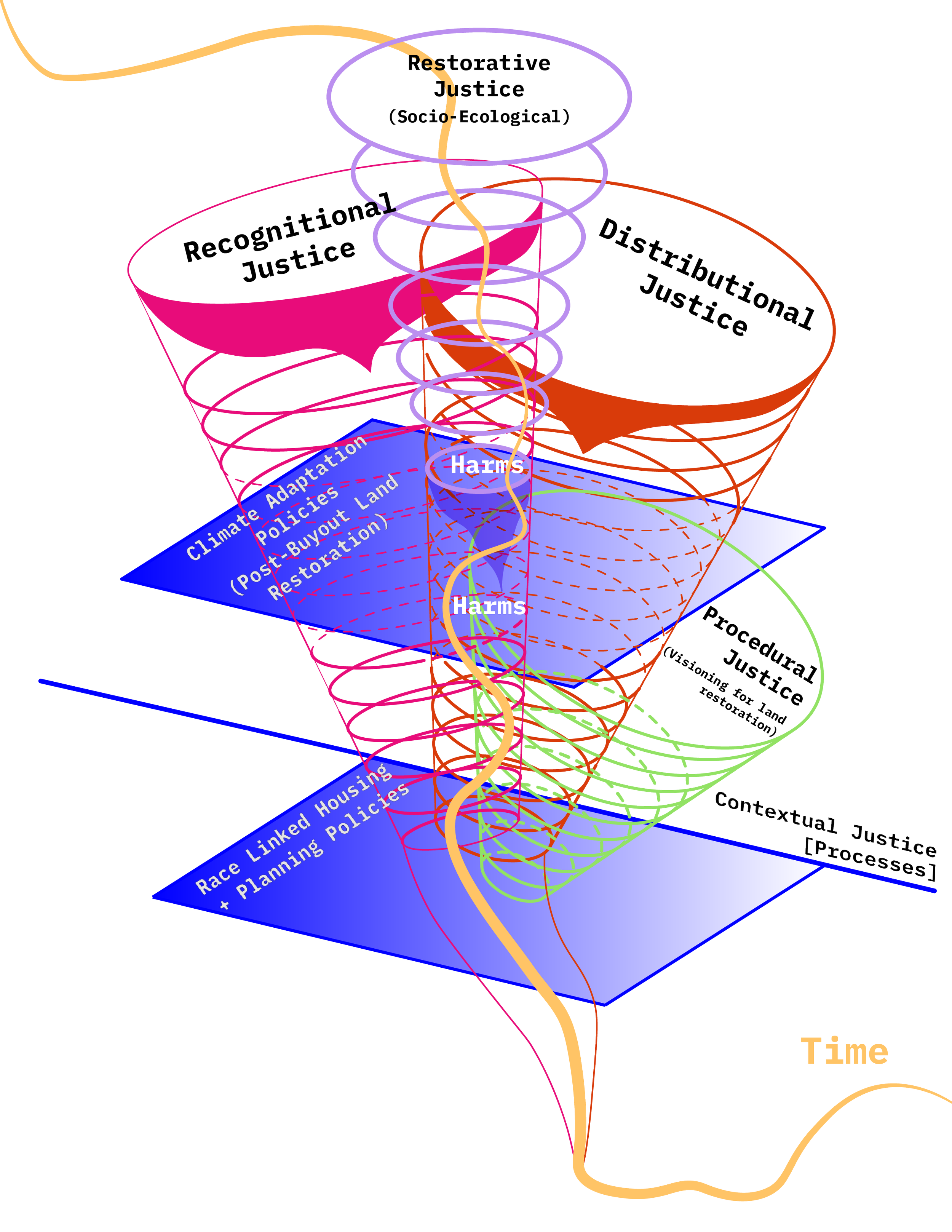

Framework of relationships between justice dimensions. Image by Veronica Olivotto with Claudia Tomateo.

While I was doing background research about Edgemere (Queens, NYC), I discovered statistics on limited access to fresh produce and commercial spaces, revealing a history of neighborhood disinvestment. This made "senses of justice" an ideal concept—a non-prescriptive container for residents' perceptions about their neighborhood, vacant land, flood risk, and managed retreat. It enabled critical knowledge production centered on resident experiences rather than outsider assumptions.

Cycles of Injustice: How Historical Neglect Undermines Climate Adaptation

My research revealed vicious cycles among dimensions of justice that profoundly impact climate adaptation efforts. Systemic contextual injustices like neighborhood segregation and disinvestment create distributional inequities in housing, food security, and healthcare. These structural injustices make recovering from climate impacts extremely challenging, and contribute to sustained feelings of trauma, mistrust, and neglect within the community.

Senses of Justice and Community Visioning at the Edge of the Sea. Poster conceptualized by Veronica Olivotto, designed by Claudia Tomateo.

From these structural injustices emerge powerful experiential feelings—of betrayal, disrespect, and abandonment. These emotional responses aren't merely subjective; they reflect real histories of institutional neglect and have tangible consequences for community organizing. The divisions between renters and homeowners, emerging from pre-existing neighborhood segregation, contribute to fragmented civic action and make it difficult to mobilize residents around shared concerns, including post-retreat land use planning.

Perhaps most revealing was the discovery that NYC, like many local governments, lacks any coherent strategy for post-buyout land restoration. Edgemere's buyout lots remain vacant 12 years after Superstorm Sandy, compounding feelings of betrayal. When a national conservation organization funded community visioning workshops led by the Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity (RISE), residents developed creative ideas for recreational, economic, and food-related uses of vacant lands. However, the city merely endorsed the project without committing resources or approving implementation—effectively perpetuating decades of neglect.

Building Trust Through Gardens: My Immersive Methodology

Understanding vacant land perceptions and conditions after retreat required spending extensive time in Edgemere, but gaining deeper insights about flood risk and institutional abandonment demanded building substantial trust with residents. Volunteering at a local community garden and with RISE provided authentic opportunities for connection beyond typical researcher-subject dynamics.

The most successful interviews occurred with people I'd worked alongside—planting flowers, surveying land, or doing community outreach. The garden especially became a space where residents felt comfortable discussing concerns, seeking help, and building kinship. Volunteering created opportunities for shared moments of solace and mutual trust—opening space for deeper conversations about flood risk, displacement, and belonging that wouldn’t have emerged in interviews alone.

The Urban Systems Lab's connections with city agencies facilitated some official interviews, though most relationships with community members I built from scratch. My time at the lab also resulted in co-authoring a paper on the uneven distribution of vulnerability across environmental justice areas in NYC, which greatly influenced how I analyzed vulnerability in Edgemere, see Shifting landscapes of coastal flood risk: environmental (in)justice of urban change, sea level rise, and differential vulnerability in New York City.

Reimagining Retreat: A Holistic Approach to Climate Migration

My findings point to the urgent need for comprehensive and neighborhood-specific managed retreat strategies. Retreat policy must move beyond property transactions to embrace housing mobility—recognizing that successful relocation depends on affordable housing availability outside flood zones. New York City's 2022 Waterfront Vision policy begins to address this by bundling housing counseling, moving support, and payment assistance.

These services should be preventative, helping households understand retreat options before disasters strike. As Rachel Kimbro's research shows, decisions about home elevation or demolition become extraordinarily difficult when families are already coping with loss and trauma.

A truly comprehensive approach also requires strategic selection of buyout lots as part of long-term, incremental retreat planning that considers both ecological attributes and socio-economic impacts on remaining residents. This demands clarity about land restoration potential and obstacles—something missing in Edgemere's case.

Each neighborhood requires tailored strategies reflecting its unique socio-economic profile, service access, and community organizing capacity. In Edgemere, historical disinvestment has created deep mistrust that permeates both physical infrastructure and emotional landscapes. Many residents I interviewed were first-time African-American homeowners who view retreat as yet another form of disrespect, preferring in-place protection. We need decision making frameworks that are able to balance flood risk management with community and ecological health. Ecological functions could integrate social amenities that are deemed valuable for those who remain in place.

The Role of Restorative Justice and Deliberative Approaches in Managed Retreat

Looking forward, I'm interested in exploring how ecological restoration work might serve as a form of relational reparation in historically disinvested communities. Restorative justice involves practices that rebuild trust through acknowledgment of past wrongs, power asymmetries, and deliberative processes centered on community opinions, experiences and expectations. Restoration projects where planning and implementation are shared between professionals and local residents could help rebuild trust, especially if they also acknowledge past wrongs and local power imbalances.

If restorative justice is about repairing relations then it requires humility and slowing down decision making about the future to create safe spaces where emotions can be voiced and heard. I'm particularly interested in "mini-publics" and other deliberative processes that facilitate dialogue across different knowledge forms and collectively define the common good. Mini publics should be carefully designed, accounting for steps in the process that could trigger power inbalances such as agenda setting, choice of experts, storytelling, group composition, and facilitation. Such approaches should be combined with more transparent and accountable city decision making processes. The Uniform Land Use Reform Process (ULURP) and the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) are the only two methods through which citizens can interact with land use and environmental decision making. Neither are conducive to genuine public input, serious deliberation, or decision‐making in the public interest. The time is ripe for innovations in governance and deliberation instruments in NYC; the complexity of climate change risks and impacts demand changes in power structures underlying coastal adaptation decision making.

Why This Research Matters for Climate Justice

My work fills a critical gap in managed retreat literature by centering those left behind, contextualizing their experiences within broader patterns of environmental justice , and capturing how communities experience and navigate life in neighborhoods marked by vacant land and institutional neglect. By integrating resident perspectives with urban planning approaches, this research offers insights that can inform more inclusive and historically aware approaches to post-buyout land use and climate adaptation. A climate and housing mobility agenda for NYC needs to understand preventatively under what conditions different social groups may accept buyouts. In line with other scholars, this research shows that factors like place attachment, compensation amounts , and ability to secure comparable housing outside of risk zones greatly influence decisions to move. Stated preference surveys could help identify more acceptable program configurations and clarify their role within broader risk management portfolios.

As climate change intensifies flooding threats in coastal communities worldwide, ensuring equitable retreat and restoration processes becomes increasingly urgent. My research reinforces existing arguments over how effective adaptation and effective climate mobility requires addressing not just physical vulnerability but the complex social, emotional, and historical dimensions of place—particularly in communities where environmental justice remains elusive.

Edited by Valérie Lechêne